PUNDITA RAMABAI SARASVATI

*Pundita is a title, a feminine form of “learned master”, but apparently so is “Sarasvati.”

WITH INTRODUCTION BY

RACHEL L.

BODLEY, A.M., M.D.,

DEAN OF WOMAN’S

MEDICAL COLLEGE OF PENNSYLVANIA

PHILADELPHIA

1887

Dedication

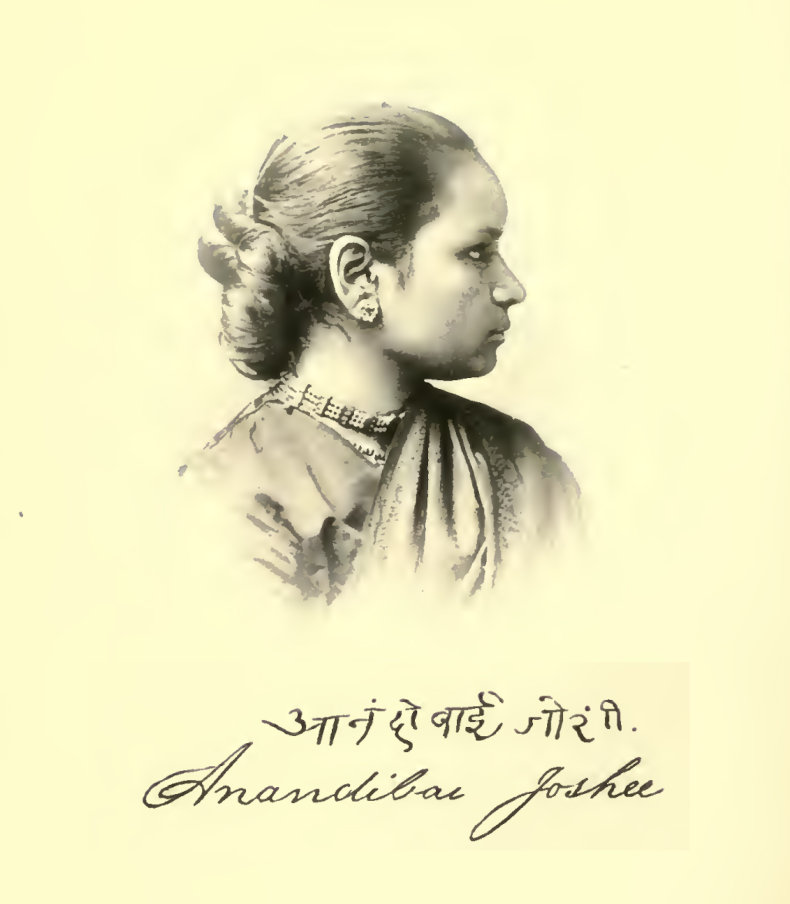

In Memoriam: Dr Anandibai

Joshee

Introduction

1. PREFATORY REMARKS

2.

CHILDHOOD

3. MARRIED LIFE

4. WOMAN’S PLACE IN RELIGION AND SOCIETY

5. WIDOWHOOD

6. HOW THE

CONDITION OF WOMEN TELLS UPON SOCIETY

7.

THE APPEAL

End Notes

To the memory of

My beloved Mother,

LAKSHMÎBAI DONGRE,

whose sweet influence and able instruction

have been the light

and guide of my life,

this little volume

is most reverently

dedicated

ANANDIBAI JOSHEE, M. D

Daughter Of

GANPATRAO AMRITASWAR and GUNGABAI JOSHEE

Born in Poona, Bombay Presidency, India, March 31st, 1865. (Maiden name, Yamuna Joshee.)

Married Gopalrao Vinayak Joshee, March 31st, 1874. (Married name, Anandibai Joshee.)

Sailed from Calcutta, India, for America, April 7th, 1883, being the first high-caste Brahman woman to come to the United States. Landed in New York, June 4th, 1883.

Graduated in medicine, from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, March 11th, 1886, being the first Hindu woman to receive the Degree of Doctor of Medicine in any country.

Appointed, June 1st, 1886, to the position of Physician-in-Charge of the Female Ward of the Albert Edward Hospital, in the City of Kolhapur, India.

Sailed from New York, to assume her duties in Kolhapur, October 9th, 1886.

Died in Poona, India, February 26th, 1887.

The silence of a thousand years has been broken, and the reader of this unpretending little volume catches the first utterances of the unfamiliar voice. Throbbing with woe, they are revealed in the following pages to intelligent, educated, happy American women.

God grant that these women, whom He has blessed above all women upon the earth, may not flippantly turn away, as they are wont to do from some over-pious tale, and without reading, condemn! To begin this story of The High-caste Hindu Woman, and not to read it through attentively to the last word of the agonized appeal, is to invoke upon oneself the divine displeasure meted out to those who disregard the cry of “him that had none to help him.” These lines are written with deep emotion; the blinding tears which fall upon the page are the saddest tears my eyes have ever wept.

From childhood I had been familiar with the statements concerning the condition of the native women of India. My sympathies had always been with them, and my annual offering to the treasury of missionary societies which worked among them, had never been omitted; but in September, 1883, there came to my door a little lady in a blue cotton saree, accompanied by her faithful friend, Mrs. B. F. Carpenter, of Roselle, New Jersey, and since that hour, when, speechless for very wonder, I bestowed a kiss of welcome upon the stranger’s cheek in lieu of words, I have loved the women of India. The little lady was Mrs. Anandibai Joshee. Less than three months ago, the wealthy and conservative city of Poona, India, which gave her birth, was stirred as never before to honor a woman, and amid the pomp of Brahminical funeral rites performed by orthodox Hindu priests, her funeral pile was lighted from the sacred fire, in the presence of a great throng of sorrowing Hindus. She sealed with her early death the superhuman effort to elevate her countrywomen and to minister in her own person to their physical needs.

To witness Dr. Joshee’s graduation in medicine, there came to Philadelphia from England her kinswoman, Pundita Ramabai Sarasvati. The two ladies never met until they greeted each other under my roof, March 6th, 1886; but, as kindred spirits, they had corresponded for several years. Strangely enough, each left India without the knowledge of the other, and within the same month, Mrs. Joshee sailing from Calcutta [Kolkata] and the Pundita from Bombay [Mumbai]. The day that Mrs. Joshee left Liverpool for New York, Ramabai and her little daughter landed in England. The reception of the two ladies in the summer of 1883, one in England and the other in the United States, was most cordial; and, comforted and blessed as neither had dared to anticipate before leaving India, each settled down to work with industry and with a degree of intelligence which was a revelation to onlookers.

My own personal experience relates to her who fell to our lot in the college in Philadelphia. She tried faithfully, this little woman of eighteen, to prosecute her studies, and at the same time to keep caste-rules and cook her own food; but the anthracite coal-stove in her room was a constant vexation, and likewise a source of danger; and the solitude of the individual house-keeping was overwhelming. In her father’s house, the congregate system, referred to in this book, prevailed; and, being a man of means, the family was always large. Later, when under her husband’s care, he had been in the postal service, and the dwelling apartments were in the same building with the post-office; hence she had never known complete solitude. After a trial of two weeks, her health declined to such an alarming extent that I invited her to pay a short visit in my home, and she never left it again to dwell elsewhere in Philadelphia during her student residence. In the performance of college duties, going in and out, and up and down, always in her measured, quiet, dignified, patient way, she has filled every room, as well as the stairways and halls, with memories which now hallow the home, and must continue so to do throughout the years to come.

In the spring of 1884, Mrs. Joshee accepted an invitation to address an audience of ladies convened for a missionary anniversary, and she chose as her subject “Child Marriage,” and surprised her great audience by defending the national custom. If there are any who still cherish the feelings of disappointment and regret engendered that April afternoon, let them turn to Ramabai’s chapter on Married Life in this book, and learn how absolutely impossible it was for a high-caste Hindu wife to speak otherwise. Let them also discover, in the herculean attempt of that occasion, a clue to the influences which at length overpowered and slew this gentle, grave woman.

“I will go (to America) as a Hindu, and come back and live among my people as a Hindu.” Brave, patriotic words! a resolve which was carried out to the death. Ramabai’s chapter on Married Life, the married life of a Hindu woman in the year 1887, no less than in past centuries, reveals to the Western reader what it was for this refined, intellectual woman, whose faculties developed rapidly under Western opportunities, and whose scientific acquirements placed her high in rank among her peers in the college class, to accept again the position awarded her by the Code of ManuThe Manusmṛiti (Sanskrit: मनुस्मृति), also known as the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra or Laws of Manu, is one of the many legal texts of Hinduism. It belongs to the Dharmaśāstra (literally, “science of right living”) literary tradition (Manu ix. 22) (See p. 40). That she did accept it, that “until death she was patient of hardships, self-controlled, … and strove to fulfill that most excellent duty which is prescribed for wives,” is undoubted. She battled hand to hand with every circumstance, resolved, as a Hindu, to live and work for the uplifting of her sisters, but all in vain!

After years of exile, she found herself once more in the familiar places of her childhood, surrounded by her mother and maternal grandmother and sisters. She had returned to them too late to admit of the restoration of her appetite by the nourishing food their skillful hands knew how to prepare; but in love they watched beside her, and it was the dear mother’s privilege to support the daughter in her arms when at midnight the end came quickly. This occurred February 26th, 1887, in the city of Poona, in the house in which she was born. Previous to the cremation of the body, which took place the morning following her death, her husband had a photograph taken of “matter before it was transformed into vapor and ashes.” The pathos of that lifeless form is indescribable. The last of several pictures, taken during the brief public career of the little reformer, it is the most eloquent of them all. The mute lips, and the face, wan and wasted and prematurely aged in the fierce battle with sorrow and pain, alike convey to her American friends this message, not to be forgotten: “I have done all that I could do.” Ah! who will thus early dare to say that she has not accomplished more by her death than she might have accomplished by a long life? Herself and husband returned from a foreign land, where they had dwelt with a strange people, ought, by Hindu custom, to have been treated as outcasts, and their shadows shunned. Instead, when it was known that the distinguished young Hindu doctor had reached her early home, old and young, orthodox and non-orthodox, came to pay friendly visits and to extend a cordial welcome.

Even the reformers were astounded when they beheld the manner in which the travelers were treated by the most orthodox families. The papers from day to day chronicled the state of the invalid’s health, and when at length she passed away, several of the journals of Poona printed in the vernacular, contained under symbols of mourning, eulogistic notices of her character and work. Ramabai has translated two of these for me, and from them I make extracts:

“Dr. Anandibai Joshee has left us to abide in the next world; but the example she has set will not be fruitless. It is indeed wonderful that a Brahmin lady has proved to the world that the great qualities – perseverance, unselfishness, undaunted courage and an eager desire to serve one’s country – do exist in the so-called weaker sex. We ought as a people to do something that will remind us of her and bear witness forever to her wondrous virtues; in our opinion, this debt of gratitude to Anandibai cannot be better discharged than by providing a lady, who will be willing to study medicine, with all the pecuniary aid necessary. Thus may the memory of the late distinguished lady be perpetuated.” Kesari, February 27, 1887.

“One of the great and grievous losses which our unfortunate Hindustan incessantly sustains was witnessed by Poona, we grieve to say, on Saturday last, when Dr. Anandibai Joshee was summoned from this world late in the midnight. She has been residing in Poona for the last two months; she came hither in the hope that her native city, which has many renowned physicians residing in it, might prove for her a healthy place, and that the pleasant weather and home influences would all contribute towards improving her health. The hopeful expectations of her countrywomen, who had looked forward to the day when they would be benefited by Dr. Joshee’s remarkable ability and well-earned knowledge, are now wholly dissipated.”

“Although Anandibai was so young, her perseverance, undaunted courage and devotion to her husband were unparalleled. We think it will be long before we shall again see a woman like her in this country. We do not hesitate to say that Dr. Joshee is worthy of a high place on the roll of historic women who have striven to serve and to elevate their native land. … The education that she had received had greatly heightened her nature and ennobled her mind. Although she suffered more than words can express from her mortal disease, phthisis, not a word either of complaint or impatience escaped her lips at any time. After months of dreadful suffering she was reduced to skin and bone, and every one that looked at her could not but be greatly pained; yet, wonderful to relate, Anandibai thought it her present duty to suffer silently and cheerfully. … After the picture was taken, her relatives bathed the body and decked it with bright garments and ornaments, according to Hindu custom. There was no time to spread the sad news throughout the city, but as many as heard it accompanied her remains to the cremation ground, thus showing the respectful affection they felt for her. Some people had feared that the priests might raise objections to cremating her body in the sacred fire, according to the Hindu rites; but these fears proved groundless. Not only on the occasion of her cremation, but earlier during her lifetime, when her husband offered sacrifices to the gods and the guardian planets to avert their anger and her death, the priests showed no sign of any prejudice against them; they gladly officiated in the religious sacrifices, thus affording a remarkable proof of their advanced views. After the body was placed upon the funeral pile Mr. V. M. Ranade made an oration in Dr. Joshee’s honor, and the cremation was then completed without hindrance.” Dnyana Chakshu, March 2nd, 1887.

The general public interest in the person and work of Dr. Joshee is a sufficient reason for presenting in this introductory chapter the above details, which have not elsewhere been given to her American friends. Pundita Ramabai, her beloved and trusted kinswoman, still lives to perform, not her identical work, but to prosecute the general disenthrallment of Hindu women, concerning the ultimate accomplishment of which Dr. Joshee cherished invincible faith. Greatly bereaved, her fond hopes of a congenial supporter and an efficient helper in India suddenly dashed to the ground, Ramabai toils on with a heroic singleness of purpose. It is in the prosecution of this one supreme object of helping her countrywomen to a better and higher life that this little book has been written. In her contact with American philanthropists and educators, during the year of her sojourn in the United States, Ramabai has found popular ideas concerning the women of India erroneous, and it is to correct these, and also to reveal fully their needs, that the following chapters have been prepared.

She has written in the belief that if the depths of the thralldom in which the dwellers in Indian zenanas are held by cruel superstition and social customs were only fathomed, the light and love in American homes, which have so comforted her burdened heart, might flow forth in an overwhelming tide to bless all Indian women. The task of preparing The High-caste Hindu Woman has not been for her a congenial one. She is not by nature an iconoclast. She loves her nation with a pure, strong love. But her love has reached the height where it is akin to the motive of the skillful surgeon: she dares to inflict pain because she regards pain as affording the only sure means of relief. She is satisfied, moreover, that India cannot arise and take her place among the nations of the earth until she, too, has mothers; until the Hindu zenana is transformed into the Hindu home, where the united family can have “pleasant times together.” (See p.48)

There are readers who, upon the title-page of this book, will see the Pundita’s name for the first time, and all such will naturally inquire, Who is she? In view of the fact, that she seeks to assume grave responsibilities before the American public this question is legitimate, and therefore, at the risk of growing tedious, I will endeavor to make answer. It is a weird beginning of a life-sketch to ask the inquirer to read of an occurrence (on page 37), in the early morning, on the banks of the sacred river Godavari. The fine-looking man who came to the river-side to bathe was the learned Ananta Shastri, and the little girl of nine, whom he carried away the day following as his child-bride, was Ramabai’s mother. This Brahmin pundit, who “well and tenderly cared for the little girl beyond all expectation,” was a native of the Mangalore district in Western India. In his boyhood, when about ten years of age, he had been married, and had brought his child-bride to his mother’s house and committed the little girl to her keeping. He, however, was possessed with a desire for the acquisition of knowledge, and attracted by the fame of Ramachandra Shastri, a distinguished scholar, who dwelt in Poona, he early made his way thither, and sought his instruction. This eminent Brahmin had been employed by the reigning Peshwa to visit his palace statedly, and give Sanskrit lessons to a favorite wife. The student Ananta was privileged to accompany his teacher, and, thus going in and out of the palace, he occasionally heard the lady reciting Sanskrit poems.

The boy was filled with wonder that a woman should be so learned, and as time wore on, astonishment gave place to admiration of her learning, and he resolved that he would teach his little wife just as the Shastri taught the fair Rani of the palace. His student-life ended at the age of twenty-three, and he hastened to his native village to incorporate education with his duties as a householder. But the bride had no desire to be instructed; his mother and all the elders of the family demurred, and the husband was compelled to desist. The married life went on, children were born to the young couple, and at length the wife died. The widower had not forgotten the Peshwa’s palace in Poona and the Sanskrit poems, and he resolved to begin his next experiment early.

We learn from the printed page how he accepted the little bride of nine who was offered to him, and carried her to his distant home; there he delivered her to his mother, and immediately began to teach her Sanskrit. But the elders of the household objected as before; the little wife was too young to have a voice in the matter, and the husband resolved that the experiment of the girl’s education should be faithfully carried out. He therefore left the valley and civilization below him, and journeyed upward with his young wife to the forest of Gungamul, on a remote plateau of the Western Ghauts, and literally in the jungle, took up his abode. Ramabai relates as a memory of her childhood her mother’s recital of how the first night was spent in the sylvan solitude, without shelter of any kind. A great tiger came with the darkness, and from across a ravine, made the night hideous with its cries. The little bride wrapped herself up tight in her pasodi (cotton quilt) and lay upon the ground convulsed with terror, while the husband kept watch until daybreak, when the hungry beast disappeared. The wild animals of the jungle were all about them, and hourly terrified the lonely little girl; but the lessons went on without hindrance, and day by day the wife, Lakshmibai, grew in stature and in knowledge. A rude dwelling was constructed, and after a few years little children came to the home in the forest, one son and two daughters. The father devoted himself to the education of the son and elder daughter, and also to that of young men who, as students, sought out the now famous Brahmin priest, whose dwelling-place in the mountains, at the source of one of the rivers, was regarded as sacred, and hence a place of pilgrimage for the pious. When Ramabai, the youngest child, was born, in April, 1858, the father was quite too much occupied to instruct her, and, moreover, he was growing old. Upon her mother, therefore, devolved the instruction in Sanskrit.

The resident students and the visiting pilgrims and the aged father and mother-in-law, now members of the family, as well as the children of the household, entailed many cares upon the educated Hindu mother, and the only time that could be found for the little daughter’s lessons was in the morning twilight, before the toilsome day had dawned. Ramabai recalls with emotion that early instruction while held in her dear mother’s arms. The little maiden, heavy with sleep, was tenderly lifted from her bed upon the earth, and wakened with many endearments and sweet mother-words; and then, while the birds about them in the forest chirped their morning songs, the lessons were repeated, no other book than the mother’s lips being used. It is these lessons of the early morning, statedly renewed with each recurrent day, that constitute the fountain-head of the “sweet influences and able instruction” which, in the dedicatory page of this book, the author characterizes as “the light and guide of my life.”

But this was a Hindu home, not an American home where such kindly care and wise parental love would have borne for the parents refreshing fruit in their old age. The father, under the iron rule of custom, had given his elder daughter in marriage when very young, and upon pages 62 and 63 we learn the nature of the sorrows which overtook the family; previous to this, however, the popularity of the Shastri as a teacher, and his sacred locality in the wilderness, had involved him in debt; for guests must be fed and duties enjoined by religion performed, at whatever pecuniary loss. The half of his landed property in his native village, which was to be the portion of the son by the second wife, was, with the son’s consent, sold to discharge the debts, and then the family, homeless, set out upon pilgrimages. It is difficult for the Western reader, with whom the word home is inseparable from family existence, to realize that this Hindu family were thus employed seven years, Ramabai being nine years of age when they set out.

But all the while as this Marathi priest and his wife and children wandered from one sacred locality to the next, having no certain dwelling-place, the early morning lessons were continued, and Ramabai, developing rare talent, became, under the instructions of father and mother, “a prodigy of erudition.” Engrossed in her studies, she was allowed to remain single until the age of sixteen, when, within a month and a half of each other, her parents died.

“From my earliest years,” Ramabai states, “I always had a love of books. Though I was not formally taught Marathi, yet hearing my father and mother speak it and being in the habit of reading newspapers and books in that language, I acquired a correct knowledge of it. In this manner I acquired also the knowledge of Kanarese, Hindustani and Bengali while traveling about. My father and mother did not do with me as others were in the habit of doing with their daughters, i. e., throw me into the well of ignorance by giving me in marriage in my infancy. In this my parents were both of one mind.” When death invaded the pilgrim household, the father, bowed with age and now totally blind for several years, was taken first; in six weeks the mother followed. The poverty of the family was extreme; consequently, Brahmins could not be secured to bear the remains to the burning-ghat, which was three miles distant from the scene of the mother’s death. At length two Brahmins were found who took pity upon them, and with the assistance of these men, the devoted son and daughter themselves carried the precious burden to the distant place of cremation, Ramabai’s low stature compelling the bearing of her share of the burden upon her head. Why do I recount this passage of nameless woe? Why? Because we American women, in our own homes, have never before looked into the face of one upon whom a ministry of sorrow so overwhelming as this has been laid, and we need, in our prosperity, to realize that God hath made of one blood all nations of men. The lovely woman who writes this book in the city of Philadelphia and the beloved mother to whom she dedicates it were in the forest of Gungamul and in the later, dusty paths of pilgrimage alike destitute of the true knowledge of God; but, in their great spiritual darkness, they ministered to and mutually loved and cherished each other with that maternal and filial affection which is the same the world over.

After the death of the parents and the elder sister, Ramabai and her brother continued to travel. They visited many countries on the great continent of India, the Punjab, Rajputana, the Central Provinces, Assam, Bengal and Madras, and, as pilgrims, were often in want and distress. They spent their time in advocating female education, i.e., that before marriage high-caste Hindu girls should be instructed in Sanskrit and in their vernacular, according to the ancient Shastras, [compendium of knowledge].

When, in their journeying, they at length reached Calcutta, the young Sanskrit scholar and lecturer created a sensation by her advanced views and her scholarship. She was summoned before the assembled pundits of the capital city; and as a result of their examination the distinguished title of Sarasvati was publicly conferred upon her by them. Soon after, her brother died. “His great thought during his brief illness,” she writes, “was for me; what would become of me left alone in the world? When he spoke of his anxiety, I answered: ‘There is no one but God to care for you and me.’ ‘Ah,’ he answered, ‘then if God cares for us, I am afraid of nothing.’ And, indeed, in my loneliness, it seemed as if God was near me; I felt His presence.” “After six months I married a Bengali gentleman, Bipin Bihari Medhavi, M.A., B.L., a Vakil and a graduate of the Calcutta University. But we neither of us believed either in Hinduism or Christianity, and so we were married with the civil marriage rite … After nineteen months of happy married life, my dear husband died of cholera. This great grief drew me nearer to God. I felt that He was teaching me, and that if I was to come to Him, He must Himself draw me.” A few months before the husband’s death a little daughter was born in the happy home – a daughter greatly desired by both father and mother before her birth, and hence, she found a beautiful name awaiting her, – Manorama, Heart’s Joy.

The widow Ramabai now returned to her former occupation as a lecturer. It became her especial mission to advocate the cause of Hindu women, according to what she believed to be the true rendering of the ancient Shastras, in opposition to the degraded notions of modern times. Her earnestness and enthusiasm gained her many admirers, among whom was Dr. W. W. Hunter, prominently connected with the British educational interests of India. He thought her career and the good she was doing so well worthy of admiration that he made her the subject of a lecture delivered in Edinburgh.

“When I spoke,” says Dr. Hunter, “of a high-caste Indian lady being thus employed, that great English audience rose as one man and applauded the efforts which the Pundita Ramabai was making on behalf of her countrywomen.” Henceforth her name was well known in England, as well as in India, to all who were interested in the social amelioration of the people of Hindustan.

With a view to improve the degraded condition of her countrywomen, she formed in Poona a society of ladies, known as the Arya Mahila Somaj, whose object was the promotion of education among native women, and the discouragement of child-marriage. She then went from city to city throughout the Bombay Presidency, establishing branch societies and arousing the people by her eloquent appeals. When the English Education Commission visited Poona in September, 1882, for the purpose of inspecting the educational institutions of that city, the leading Brahmin ladies, members of the newly-formed society and others, to the number of about three hundred, assembled with their children in the Town Hall, to welcome the Commission and to show them that, although the municipality had not encouraged girls’ schools, a genuine movement was being inaugurated by the best families of the Marathi country. Pundita Ramabai was the orator of the occasion.

Dr. Hunter, as President of the Education Commission, made Ramabai the prominent figure among the many noteworthy persons who were examined before him during that visit. He regarded her evidence as of so much importance that he caused it to be translated from Marathi and separately printed. A copy of this India print is before me as I write. There are three questions, viz.:–

Question 1.– State what opportunities you have had of forming an opinion on the subject of Education in India, and in what province your experience has been gained?

Here follows, in reply, a brief, but remarkably clear, narrative of her parentage, her father’s views, those of her brother, also a statement in regard to her husband, and the vicissitudes of her life; all of which, she stated, had afforded her many opportunities of forming an opinion on the subject of Female Education in different provinces of India. She closes thus:–

“I am the child of a man who had to suffer a great deal on account of advocating Female Education, and who was compelled to discuss the subject, as well as to carry out his own views, amidst great opposition. … I consider it my duty, to the very end of my life, to maintain this cause, and to advocate the proper position of women in this land.”

Question 2. What is the best method of providing teachers for girls?

Answer 2. It appears to me evident that the women who are to become teachers of others should have a special training for that work. Besides having a correct knowledge of their own language, they ought to acquire English. Whether those training to be female teachers are married or unmarried, or widows, they ought to be correct in their conduct and morals, and they ought also to be of respectable families. They ought to be provided with good scholarships. Teachers of girls also ought to have higher salaries than those of boys, as they should be of a superior character and position. The students should live in the college compound, so as to have their manners and habits improved, and there ought to be a large building with every appliance for the comfort of the teachers and students. They ought to have a native lady of good position over them. Mere learning is not enough; the conduct and morals of the students should be attended to.

Question 3. What do you regard as the chief defects, other than any to which you have already referred, that experience has brought to light in the educational system as it has been hitherto administered? What suggestions have you to make for the remedy of such defects?

Answer 3. There ought to be female inspectresses over female schools. These ought to be of the age of thirty or upwards, and of a very superior class, and highly educated, whether Native or European. Male inspectors are unsuitable for the following reasons:– (i) The women of this country are very timid. If a male inspector goes into a female school, all the women and girls are thrown into confusion, and are unable to speak. The inspector seeing this state of things will write a bad report of the school and teachers, and so in all probability Government will appoint a male teacher for that school, and so the school will not have the advantage of a female teacher. As the education of girls is different from that of boys, female schools ought to be in the hands of female teachers. (2) The second reason is this. In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the educated men of this country are opposed to Female Education and the proper position of woman. If they observe the slightest fault, they magnify the grain of mustard-seed into a mountain, and try to ruin the character of a woman; often the poor woman, not being very courageous, and well informed, her character is completely broken. Men being more able to reach the authorities are believed, while women go to the wall. Both should be alike to a parental Government, whose children, male and female, should be treated with equal justice. It is evident that women, being one-half of the people of this country, are oppressed and cruelty treated by the other half. To put a stop to this anomaly is worthy of a good Government. Another suggestion I would make is with regard to lady-doctors. Though in Hindustan there are numbers of gentleman-doctors, there are no ladies of that profession. The women of this country are much more reserved than in other countries, and most of them would rather die than speak of their ailments to a man. The want of lady-doctors is, therefore, the cause of hundreds of thousands of women dying premature deaths. I would, therefore, earnestly entreat of our Government to make provision for the study of medicine by women, and thus save the lives of those multitudes. The want of lady-doctors is one very much felt and is a great defect in the Education of the women of this country.

The answers to these questions are introduced in full, as bearing valuable and ample testimony to the character, and the position before the public, of Ramabai in her own country. Upon the authority of the Times of India, it may be stated that her plea for women-physicians before the Commission, in September, 1882, (See Answer 3), is believed to have attracted the attention of her gracious Majesty, the Queen-Empress, and to have been indirectly the origin of the movement in Hindustan which, in its latest developments, has reached the noble proportions of The National Association for Supplying Female Medical Aid to the Women of India, popularly known as the “Countess of Dufferin Movement,” from its distinguished president, the wife of the Viceroy of India.

Ramabai now realized that she herself needed personal training to enable her to prosecute with success her work among the women of India in behalf of education. Then, too, as she had in her experience become conscious of God’s guidance, her spirit was possessed of that unrest which is the solemn movement of the soul Godward, seeking “the Lord if haply she (they) might feel after Him and find Him.” “I felt a restless desire to go to England,” she writes. “I could not have done this unless I had felt that my faith in God had become strong: it is such a great step for a Hindu woman to cross the sea; one cuts oneself always off from one’s people. But the voice came to me as to Abraham. … It seems to me now very strange how I could have started as I did with my friend and little child throwing myself on God’s protection. I went forth as Abraham, not knowing whither I went. When I reached England, the Sisters in St. Mary’s Home at Wantage kindly received me. There I gradually learned to feel the truth of Christianity, and to see that it is a philosophy, teaching truths higher than I had ever known in all our systems; to see that it gives not only precepts, but a perfect example; that it does not give us precepts and an example only, but assures us of divine grace, by which we can follow that example.” True to her honest nature, she acted promptly upon her convictions and embraced Christianity, and she and her little daughter were baptized in the Church of England, September 29th, 1883. Henceforth she devoted herself to educational work. The first year was spent at Wantage in the study of the English language, which hitherto had been unknown to her. Acquiring this, she entered, September, 1884, the Ladies’ College at Cheltenham, where a position was assigned her as Professor of Sanskrit. Her unoccupied time was spent as a student of the college, in the study of mathematics, natural science, and English literature. Her opportunities at Cheltenham College were of the highest order, and the influence of the noble Christian women with whom she was associated, both there and at Wantage, was most refined and salutary in its character. She made rapid progress in her studies, and a possible Government educational appointment in India loomed up in the near future, when an invitation reached her to witness Mrs. Joshee’s graduation in medicine in Philadelphia, March 11th, 1886.

That “holy land called America” had long held attractions for her, and these were now heightened by the presence and work of her beloved kinswoman. After some weeks of painful indecision, she decided to accept the invitation, her sole reason for allowing her studies to be interrupted thus inopportunely being her thorough conviction that it was her duty in the interests of her countrywomen to visit America at that time. In February, 1886, she again embarked upon an unknown sea, accompanied by her young daughter, then nearly five years of age. Her residence in America and her public service here have been widely chronicled in the daily and weekly journals, and are not therefore a matter of private record. In the beginning she expected to return to England after a brief vacation, and there resume her studies; but, as the genius of American institutions was revealed through personal inspection, her interest grew, and she decided to prolong her stay. In midsummer she wrote: “I am deeply impressed by and am interested in the work of Western women, who seem to have one common aim, namely, the good of their fellow-beings. It is my dream some day to tell my countrywomen in their own languages this wonderful story, in the hope that the recital may awaken in their hearts a desire to do likewise.” As her contact with a public educational system which included girls as well as boys was prolonged, her old desire to benefit her countrywomen by founding schools which combined the training of the hand with that of the head revived, and forsaking plans which regarded only the higher education of the few women in government high-schools or colleges in India, she concentrated her thoughts upon native schools founded by and for native women. Early in her residence in Philadelphia she met Miss Anna Hallowell, prominently identified with the Sub-Primary School Society (free kindergartens) of the city. This distinguished lady kindly accompanied her to several of the kindergartens, and explained methods to her with care, and also the principles upon which the system was based. Ramabai’s enthusiasm was aroused as she saw in Froebel’s teaching wondrous possibilities for her little widows. Purchasing without delay the most approved text-books and the “gifts,” she set herself to work to translate into Indian thought the games and tokens of the system, in order that she might adapt it to Hindu needs. In September, 1886, she promptly enrolled herself as a student in a kindergarten training-school, and, as her public duties have permitted, she has faithfully pursued the course of study throughout the scholastic year just ending. American school-books were a revelation to her in the beauty of their illustrations and of their letter-press and the quality of the paper upon which they are printed. In July, 1886, she set herself to work upon a series of Marathi school-books for girls, modeled after the American idea, beginning with a primer and continuing regularly up to a reader of the sixth grade. She was enthusiastic as to results, designing to illustrate with American wood-cuts, although the printing would necessarily be delayed until Bombay is reached, on account of the Marathi type required. The primer was soon finished, and much of the material for the reading books prepared, when a prudent investigation was instituted as to the cost of illustrations, and the stern fact revealed that the charming pictures were far too expensive to be dreamed of for her books.

Thus the case stands June 1st, 1887. Pundita Ramabai, the high-caste Brahmin woman, the courageous daughter of the forest, educated, refined, rejoicing in the liberty of the Gospel, and yet by preference retaining a Hindu’s care as regards a vegetable diet, and the peculiarities of the dress of Hindu widowhood, solemnly consecrated to the work of developing self-help among the women of India, has her school-books nearly ready for the printer, her plans for the organization of a school, such as she describes on page 114, well developed, and two teachers (American ladies, one a graduated kindergartner) secured. Tickets for herself and teachers might be taken for India at once, and as a result of the strong reaction which the untimely death of Dr. Joshee has set up, Ramabai, outcast though she is among her own people, might inaugurate, under favorable auspices, her work among the child-widows.

But the money is wanting. In 1793, when William Carey, the first English missionary to Asia, was about to set sail for India, he said to those about him, “I will go down into the deep mine, but remember that you must hold the ropes.” As I close this chapter, the longing fills my soul that among the favored women of this Christian land there might be found a sufficient number to hold the ropes for Ramabai, making it possible for her to go out quickly to her God-inspired work. It must not be a fitful benefaction of a few hundred or even of a few thousand dollars, but a steady holding on to the ropes, for a period of not less than ten years. They must not be let go while she in the throes of a death-struggle with superstition and caste prejudice, and feminine unwillingness to rise, is fastened to the India end.

A decade of years ago, no sane woman would have presumed to appeal to the women and young girls of this land to engage in a project such as this of Ramabai, as I now do. But how rapidly we are moving on in these last days! We read in prophecy that “the earth shall be made to bring forth in one day,” and “a nation shall be born at once;” and another sure word is written, “the people shall be willing in the day of His power.” When in that great Hindu nation about to come to the birth, the women are moved to arise in their degradation, and themselves utter the feeble cry, “Help or we perish!” it cannot be otherwise than that a corresponding multitude of women must be found elsewhere, willing, in the day of God’s power, to send the help.

There have long been in every community, women who are not in accord with the so-called missionary societies, and who never contribute to the enlightenment or to the material aid of Oriental women. Ramabai’s boarding-school for child-widows, primarily an educational scheme, may be safely taken up by such, and while they organize, and after the manner of the women’s boards of the churches, through a great network of auxiliary societies, prosecute with growing interest and zeal their child-widow school work, missionary work so-called, may be continued by the societies of every denomination, each according to its own methods, the treasuries of all being alike full.

The Pundita bears witness, in public and in private, to the good accomplished in the East by missionary lady-teachers, and it is her earnest desire not to affect unfavorably in any manner, however remote, either the treasury or the work of church societies. She seeks to reach Hindu women as Hindus, to give them liberty and latitude as regards religious convictions; she would make no condition as to reading the Bible or studying Christianity; but she designs to put within their reach in reading-books and on the shelves of the school library, side by side, the Bible and the Sacred books of the East, and for the rest, earnestly pray that God will guide them to His saving truth.

It is roughly computed that Ramabai will need about fifteen thousand dollars to fully inaugurate the work of her first school and five thousand dollars annually afterwards during the ten years for which she asks help.

So easy is it to plan, so difficult to execute! Ramabai herself offers a reasonable means by which the collection of this sum may be commenced, in the presentation of this, her only American book to the public. It has been privately printed, in order that the entire profits may accrue to her; in the hope of a possible large sale, the pages have been copyrighted and electrotyped. If, therefore, every American woman who, at any time during the last twelvemonth, has taken Ramabai by the hand, every college student who has heard the Pundita speak in college halls, every reader of this book whose heart has been stirred to compassion by the perusal of its sorrowful pages, will at once purchase a copy of the book and induce a friend to do the same, each reader being responsible for the sale of one copy, the work is done, and the large fund needed to prepay three passages to India, to purchase the illustrative material for the school-rooms, to illustrate and print the school-books, and secure the needed school-property in India, is at once assured.

Ramabai has come into my library to bid me farewell, previous to her setting out on a journey of a few days. I asked her as she arose to depart, if she had a last message for the readers of her book. “Remind them,” she replied, with animated countenance and rapid speech, as she clasped my hand “that it was ‘out of Nazareth’ that the blessed Redeemer of mankind came; that great reforms have again and again been wrought by instrumentalities that the world despised. Tell them to help me educate the high-caste child-widows; for I solemnly believe that this hated and despised class of women, educated and enlightened, are, by God’s grace, to redeem India!”

RACHEL L. BODLEY, A.M., M.D.,

DEAN OF WOMAN’S MEDICAL COLLEGE OF

PENNSYLVANIA

1400 NORTH 21st ST.,

PHILADELPHIA,

June 1st, 1887.

1

In order to understand the life of a Hindu woman, it is necessary for the foreign reader to know something of the religion and the social customs of the Hindu nation. The population of Hindustan numbers two hundred and fifty millions, and is made up of Hindus, Mahometans, Eurasians, Europeans and Jews; more than three-fifths of this vast population are professors of the so-called Hindu religion in one or the other of its forms. Among these the religious customs and orders are essentially the same; the social customs differ slightly in various parts of the country, but they have an unmistakable similarity underlying them.

The religion of the Hindus is too vast a subject to be fully treated in a few paragraphs; it may be briefly stated, however, somewhat thus:– All Hindus recognize the Vedas and other apocryphal books as the canonical scriptures. They believe in one supreme spirit, Paramatma, which is pure, passionless, omnipresent, holy and formless in its essence, but when it is influenced by Maya, or illusion, it assumes form, becomes male and female, creates every thing in the universe out of its own substance. A Hindu, therefore, does not think it a sin to worship rivers, mountains, heavenly bodies, creatures, etc., since they are all consubstantial with God and manifestations of the same spirit. Any one of these manifestations may be selected to be the object of devotion, according to a man’s own choice; his favorite divinity he will call the supreme ruler of the universe, and the others gods, servants of the supreme ruler.

Hindus believe in the immortality of the soul, inasmuch as it is consubstantial with God; man is rewarded or punished according to his deeds. He undergoes existences of different descriptions in order to reap the fruit of his deeds. When at length he is free from the consequences of his action, which he can be by knowing the Great Spirit as it is and its relation to himself, he is then re-absorbed into the spirit and ceases to be an individual; just as a river ceases to be different from the ocean when it flows into the sea.

According to this doctrine, a man is liable to be born eight million four hundred thousand times before he can become a Brahmin (first caste), and except one be a Brahmin he is not fit to be re-absorbed into the spirit, even though he obtain the true knowledge of the Paramatma. It is, therefore, necessary for every person of other castes to be careful not to transgress the law by any imprudent act, lest he be again subjected to be born eight million four hundred thousand times. A Brahmin must incessantly try to attain to the perfection of the supreme knowledge, for it is his last chance to get rid of the misery of the long series of earthly existences; the least trifling transgression of social or religious rules however renders him liable to the degradation of perpetual births and deaths.

These, with the caste beliefs, are the chief articles of the Hindu creed at the present day. There are a few heterodox Hindus who deny all this; they are pure theists in their belief, and disregard all idolatrous customs. These Brahmos, as they are called, are doing much good by purifying the national religion.

As regards social customs, it may be said that the daily life and habits of the people are immensely influenced by religion in India. There is not an act that is not performed religiously by them; a humorous author has said, with some truth, that “the Hindus even sin religiously.” The rising from the bed in the morning, the cleaning of teeth, washing of hands and bathing of the body, the wearing of garments, lighting the fire or the lamp, eating and drinking and every act of similar description, is done in a prescribed manner, and with the utterance of prayers or in profound silence. Each custom, when it is old enough to be entitled “the way of the ancients,” takes the form of religion and is scrupulously observed. These customs, founded for the most part on tradition, are altogether independent of the canonical writings, so much so that a person is liable to be punished, or even excommunicated, for doing a deed forbidden by custom, even though it be sanctioned by religion.

For example, eating the food prepared by persons of an “inferior”

caste is not only not forbidden by the sacred laws, but is sanctioned

by them.“Pure men of the first three castes shall

prepare the food of a householder” (Brahman or other high

caste).

“Or Shudras (servile caste) may prepare the food under the

superintendence of men of the first three castes.” – Apastamba II. 2,

3. I. 4.

At the present day, however, time-honored custom overrules the ancient laws, and says that a person must not eat anything cooked nor drink water polluted by the touch of a person of inferior caste. Hindus transgressing this rule instantly forfeit their caste, and must undergo some heavy penance to regain it.

Without doubt, “caste” originated in the economical division of labor. The talented and most intelligent portion of the Aryan Hindus became, as was natural, the governing body of the entire race. They, in their wisdom, saw the necessity of dividing society, and subsequently set each portion apart to undertake certain duties which might promote the welfare of the nation. The priesthood (Brahmin caste) were appointed to be the spiritual governors over all, and were the recognized head of society. The vigorous, warlike portion of the people (Kshatriya, or warrior caste) was to defend the country, and suppress crime and injustice by means of physical strength; assisted by the priesthood, they were to be the temporal governors in the administration of justice. The business-loving tradesmen and artisans (Vaisya, or trader caste) had also an important position assigned under the preceding classes or castes. The fourth, or servile class (Shudra caste) was made up of all those not included in the preceding three castes. In ancient times persons were assigned to each of the four castes according to their individual capacity and merit, independent of the accident of birth.

Later on, when caste became an article of the Hindu faith, it assumed the formidable proportions which now prevail everywhere in India. A son of a Brahmin is honored as the head of all castes, not because of his merit, but because he was born into a Brahmin family. Intermarriage of castes was once recognized as lawful, even after caste by inheritance had been acknowledged, provided that a woman of superior caste did not marry a man of an inferior caste; but now law is overruled by custom. Intermarriages cannot take place without involving serious consequences, and making the offenders outcasts.

The four principal castes“There are four castes –

Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaisyas, and Shudras.”

“Amongst these, each

preceding caste is superior by birth to the one following.” –

Apastamba I. 1, 1, 3, 4.

“The Brahmana, the Kshatriya and the

Vaisya castes are the twice-born ones, but the fourth, the Shudra, has

one birth only; there is no fifth caste.” – Manu x.4.

are again divided into clans; men belonging to high clans must not

give their daughters in marriage to men of low clans. To transgress

this custom is to lose family honor, caste privileges, and even

intercourse with friends and relatives.

Besides the four castes and their clans there are numerous castes called collectively, “mixed castes” formed by the intermarriage of members of the preceding; their number is again increased by castes according to employment, as scribe, tanner, cobbler, shoemaker, tailor, etc., etc. Even the outcasts, such for example as the sweeper, have their own distinctions, as powerful among themselves as are those of the high castes. Transgressors of caste rules are, from the highest to the lowest, subject to excommunication and severe punishment. Offenders by intermarriage, or change of faith, are without redemption. It must also be borne in mind, that if a Brahmin condescends to marry a person of lower caste, or eats and drinks with any of them, he is despised and shunned as an outcast, not only by his own caste, but also by the low-caste with whose members he has entered into such relation. The low-caste people will look upon this Brahmin as a lawless wretch. So deeply rooted is this custom in the heart of every orthodox Hindu that he is not in any way offended by the disrespect shown him by a high caste man, since he recognizes in it only what is ordered by religion. For, although “caste” is confessedly an outgrowth of social order, it has now become the first great article of the Hindu creed all over India. Thoughtful men like Buddha, Nanak, Chaitanya and others rebelled against this tyrannical custom, and proclaimed the gospel of social equality of all men, but “caste” proved too strong for them. Their disciples at the present day are as much subject to caste as are any other orthodox Hindus. Even the Mahomedans have not escaped this tyrant; they, too, are divided into several castes, and are as strict as the Hindus in their observances. Over a million Hindu converts to Christianity, members of the Roman Catholic Church, are more or less ruled by caste. The Protestant missionaries, likewise, found it difficult in early days to overcome caste prejudice among their converts, and not many years ago, in the Madras presidency, clergymen were compelled to use different cups for each separate caste when they celebrated the Lord’s Supper.

The Vedas are believed by the devout Hindu to be the eternal, self-existing Word of God, revealed by Him to different sages. Besides the Vedas there are more than twenty-five books of sacred law, ascribed to different inspired authors who wrote or compiled them at various times, and on which are based the principal customs and religious institutes of the Hindus. Among these, the code of ManuThe Manusmṛiti (Sanskrit: मनुस्मृति), also known as the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra or Laws of Manu, is one of the many legal texts of Hinduism. It belongs to the Dharmaśāstra (literally, “science of right living”) literary tradition ranks highest, and is believed by all to be very sacred, second to none but the Vedas themselves.

Although Manu and the other law-givers differ greatly on many points, they all agree on things concerning women. According to this sacred law a woman’s life is divided into three parts, viz:– 1st, Childhood; 2nd, Youth or married life; 3rd, Widowhood or old age.

2

Although the code of Manu contains a single passage in which it is written “A daughter is equal to a son,” (See Manu ix., 130), the context expressly declares that equality to be founded upon the results attainable through her son; the passage therefore cannot be regarded as an exception to the statement that the ancient code establishes the superiority of male children. A son is the most coveted of all blessings that a Hindu craves, for it is by a son’s birth in the family that the father is redeemed.

“Through a son he conquers the worlds, through a son’s son he obtains immortality, but through his son’s grandson he gains the world of the sun.” – Manu ix., 137.

“There is no place for a man (in Heaven) who is destitute of male offspring.” – Vasishtha, xvii. 2.

If a man is sonless, it is desirable that he should have a daughter, for her son stands in the place of a son to his grandfather, through whom the grandfather may obtain salvation.

“Between a son’s son and the son of a daughter there exists in this world no difference; for even the son of a daughter saves him who has no sons, in the next world, like the son’s son.” – Manu ix. 139.

In Western and Southern India when a girl or a woman salutes the elders and priests, they bless her with these words– “Mayst thou have eight sons, and may thy husband survive thee.” In the form of a blessing the deity is never invoked to grant daughters. Fathers very seldom wish to have daughters, for they are thought to be the property of somebody else; besides, a daughter is not supposed to be of any use to the parents in their old age. Although it is necessary for the continuance of the race that some girls should be born into the world, it is desirable that their number by no means should exceed that of the boys. If unfortunately a wife happens to have all daughters and no son, Manu authorizes the husband of such a woman to supersede her with another in the eleventh year of their marriage.See page 61.

In no other country is the mother so laden with care and anxiety on the approach of childbirth as in India. In most cases her hope of winning her husband to herself hangs solely on her bearing sons.

Women of the poorest as well as of the richest families, are almost invariably subjected to this trial. Many are the sad and heart-rending stories heard from the lips of unhappy women who have lost their husband’s favor by bringing forth daughters only, or by having no children at all. Never shall I forget a sorrowful scene that I witnessed in my childhood. When about thirteen years of age I accompanied my mother and sister to a royal harem where they had been invited to pay a visit. The Prince had four wives, three of whom were childless. The eldest having been blessed with two sons, was of course the favorite of her husband, and her face beamed with happiness.

We were shown into the nursery and the royal bed-chamber, where signs of peace and contentment were conspicuous. But oh! what a contrast to this brightness was presented in the apartments of the childless three. Their faces were sad and careworn; there seemed no hope for them in this world, since their lord was displeased with them, on account of their misfortune.

A lady friend of mine in Calcutta told me that her husband had warned her not to give birth to a girl, the first time, or he would never see her face again, but happily for this wife and for her husband also, she had two sons before the daughter came. In the same family there was another woman, the sister-in-law of my friend, whose first-born had been a daughter. She longed unceasingly to have a son, in order to win her husband’s favor, and when I went to the house, constantly besought me to foretell whether this time she should have a son! Poor woman! she had been notified by her husband that if she persisted in bearing daughters she should be superseded by another wife, have coarse clothes to wear and scanty food to eat, should have no ornaments, save those which are necessary to show the existence of a husband, and she should be made the drudge of the whole household. Not unfrequently, it is asserted, that bad luck attends a girl’s advent, and poor superstitious mothers in order to avert such a catastrophe, attempt to convert the unborn child into a boy, if unhappily it be a girl.

Rosaries used by mothers of sons are procured to pray with; herbs and roots celebrated for their virtue are eagerly and regularly swallowed; trees and son-giving gods are devoutly worshipped. There is a curious ceremony, honored with the name of “sacrament,” which is administered to the mother between the third and the fourth month of her pregnancy for the purpose of converting the embryo into a boy.

In spite of all these precautions girls will come into Hindu households as ill-luck, or rather nature, will have it. After the birth of one or more sons girls are not unwelcome, and under such circumstances, mothers very often long to have a daughter. And after her birth both parents lavish love and tenderness upon her, for natural affection, though modified and blunted by cruel custom, is still strong in the parent’s heart. Especially may this be the case with the Hindu mother. That maternal affection, sweet and strong, before which “there is neither male nor female,” asserts itself not unfrequently in Hindu homes, and overcomes selfishness and false fear of popular custom. A loving mother will sacrifice her own happiness by braving the displeasure of her lord, and will treat her little daughter as the best of all treasures. Such heroism is truly praiseworthy in a woman; any country might be proud of her. But alas! the dark side is too conspicuous to be passed over in silence.

In a home shadowed by adherence to cruel custom and prejudice, a child is born into the world; the poor mother is greatly distressed to learn that the little stranger is a daughter, and the neighbors turn their noses in all directions to manifest their disgust and indignation at the occurrence of such a phenomenon. The innocent babe is happily unconscious of all that is going on around her, for a time at least. The mother, who has lost the favor of her husband and relatives because of the girl’s birth, may selfishly avenge herself by showing disregard to infantile needs and slighting babyish requests. Under such a mother the baby soon begins to feel her misery, although she does not understand how or why she is caused to suffer this cruel injustice.

If a girl is born after her brother’s death, or if, soon after her birth, a boy in the family dies, she is in either case regarded by her parents and neighbors as the cause of the boy’s death. She is then constantly addressed with some unpleasant name, slighted, beaten, cursed, persecuted and despised by all. Strange to say, some parents, instead of thinking of her as a comfort left to them, find it in their hearts, in the constant manifestation of their grief for the dear lost boy, to address the innocent girl with words such as these: “Wretched girl, why didst thou not die instead of our darling boy? Why didst thou crowd him out of the house by coming to us; or why didst not thou thyself become a boy?” “It would have been good for all of us if thou hadst died and thy brother lived!” I have myself several times heard parents say such things to their daughters, who, in their turn, looked sadly and wonderingly into the parents’ faces, not comprehending why such cruel speeches should be heaped upon their heads when they had not done any harm to their brothers. If there is a boy remaining in the family, all the caresses and sweet words, the comforts and gifts, the blessings and praises are lavished upon him by parents and neighbors, and even by servants, who fully sympathize with the parents in their grief. On every occasion the poor girl is made to feel that she has no right to share her brother’s good fortune, and that she is an unwelcome, unbidden guest in the family.

Brothers, in most cases, are, of course, very proud of their superior sex; they can know no better than what they see and hear concerning their own and their sisters’ qualities. They, too, begin by and by to despise girls and women. It is not a rare thing to hear a mere slip of a boy gravely lecture his elder sister as to what she should or should not do, and remind her that she is only a girl and that he is a boy. Subjected to such humiliation, most girls become sullen, morbid and dull. There are some fiery natures, however, who burn with indignation, and burst out in their own childish eloquence; they tell their brothers and cousins that they soon are going to be given in marriage, and that they will not come to see them, even if they are often entreated to do so. Children, however, soon forget the wrong done them; they laugh, they shout, they run about freely, and are generally merry when unpleasant speeches are not showered upon them. Having little or no education, except a few prayers and popular songs to commit to memory, the little girls are mostly left to themselves, and they play in whatever manner they please. When about six or seven years of age they usually begin to help their mothers in household work, or in taking care of the younger children.

I have mentioned earlier the strictness of the modern caste system in regard to marriage. Intelligent readers may, therefore, have already guessed that this reason lies at the bottom of the disfavor shown to girls in Hindu homes. From the first moment of the daughter’s birth, the parents are tormented incessantly with anxiety in regard to her future, and the responsibilities of their position. Marriage is the most expensive of all Hindu festivities and ceremonies. The marriage of a girl of a high caste family involves an expenditure of two hundred dollars at the very least. Poverty in India is so great that not many fathers are able to incur this expense; if there are more than two daughters in a family, his ruin is inevitable. For, it should be remembered, the bread-winner of the house in Hindu society not only has to feed his own wife and children, but also his parents, his brothers unable to work either through ignorance or idleness, their families and the nearest widowed relatives, all of whom very often depend upon one man for their support; besides these, there are the family priests, religious beggars and others, who expect much from him. Thus, fettered hand and foot by barbarously cruel customs which threaten to strip him of everything he has, starvation and death staring him in the face, the wretched father of many girls is truly an object of pity. Religion enjoins that every girl must be given in marriage; the neglect of this duty means for the father unpardonable sin, public ridicule and caste excommunication. But this is not all. The girl must be married within a fixed period, the caste of the future husband must be the same, and the clan either equal or superior, but never inferior, to that of her father.

The Brahmins of Eastern India have observed successfully their clan prejudice for hundreds of years despite poverty; they have done this in part by taking advantage of the custom of polygamy. A Brahmin of a high clan will marry ten, eleven, twenty, or even one hundred and fifty girls. He makes a business of it. He goes up and down the land marrying girls, receiving presents from their parents, and immediately thereafter bidding good-bye to the brides; going home, he never returns to them. The illustrious Brahmin need not bother himself with the care of supporting so many wives, for the parents pledge themselves to maintain the daughter all her life, if she stays with them a married virgin to the end. In case of such a marriage as this, the father is not required to spend money beyond his means, nor is it difficult for him to support the daughter, for she is useful to the family in doing the cooking and other household work; moreover, the father has the satisfaction first, of having given his daughter in marriage, and thereby having escaped disgrace and the ridicule of society; secondly, of having obtained for himself the bright mansions of the gods, since his daughter’s husband is a Brahmin of high clan.

But this form of polygamy does not exist among the Kshatriyas, because, as a member of the non-Brahmin caste, a man is not allowed by religion, to beg or to receive gifts from others, except from friends; he therefore cannot support either many wives or many daughters. Caste and clan prejudice tyrannized the Rajputs of North and Northwestern and Central India, who belong to the Kshatriyas or warrior caste, to such an extent that they were driven to introduce the inhuman and irreligious custom of female infanticide into their society. This cruel act was performed by the fathers themselves, or even by mothers, at the command of the husband whom they are bound to obey in all things.

It is a universal custom among the Rajputs for neighbors and friends to assemble to congratulate the father upon the birth of a child. If a boy is born, his birth is announced with music, glad songs and by distributing sweetmeats. If a daughter, the father coolly announces that “nothing” has been born into his family, by which expression it is understood that the child is a girl, and that she is very likely to be nothing in this world, and the friends go home grave and quiet.

After considering how many girls could safely be allowed to live, the father took good care to defend himself from caste and clan tyranny by killing the extra girls at birth, which was as easily accomplished as destroying a mosquito or other annoying insect. Who can save a babe if the parents are determined to slay her, and eagerly watch for a suitable opportunity? Opium is generally used to keep the crying child quiet, and a small pill of this drug is sufficient to accomplish the cruel task; a skillful pressure upon the neck, which is known as the “putting nail to the throat,” also answers the purpose. There are several other nameless methods that may be employed in sacrificing the innocents upon the unholy altar of the caste and clan system. Then there are not a few child-thieves who generally steal girls; even the wild animals are so intelligent and of such refined taste that they mock at British law, and almost always steal girls to satisfy their hunger.

Female infanticide, though not sanctioned by religion, and never looked upon as right by conscientious people, has, nevertheless, in those parts of India mentioned, been silently passed over unpunished by society in general.

As early as 1802 the British government enacted laws for the suppression of this horrid crime; and more than forty years ago Major Ludlow, a kind-hearted Englishman, induced the semi-independent States to prohibit this custom, which the Hindu princes did, by a mutual agreement not to allow any one to force the father of a girl to give more dowry than his circumstances should warrant, and to discourage extravagance in the celebration of marriages. But caste and clan prejudice could not be overcome so easily.

Large expenses might be stopped by law, but a belief, deeply rooted in the hearts and religiously observed by the people for centuries, could not be removed by external rules.

The Census of 1870 revealed the curious fact that three hundred children were stolen in one year by wolves from within the city of Umritzar, all the children being girls, and this under the very nose of the English government. In the year 1868 an English official, Mr. Hobart, made a tour of inspection through those parts of India where female infanticide was most practiced before the government enacted the prohibitory law. As a result of careful observation, he came to the conclusion that this horrible practice was still followed in secret, and to an alarming extent.

The Census returns of 1880-81 show that there are fewer women than men in India by over five millions. Chief among the causes which have brought about this surprising numerical difference of the sexes may be named, after female infanticide in certain parts of the country, the imperfect treatment of the diseases of women in all parts of Hindustan, together with lack of proper hygienic care and medical attendance.

3

It is not easy to determine when the childhood of a Hindu girl ends and the married life begins. The early marriage system, although not the oldest custom of my country, is at least five hundred years older than the Christian era. According to Manu, eight years is the minimum, and twelve years of age the maximum marriageable age for a high caste girl.A man aged thirty years shall marry a maiden of twelve who pleases him, or a man of twenty-four a girl of eight years of age. – Manu ix., 94. The earlier the act of giving the daughter in marriage, the greater is the merit, for thereby the parents are entitled to rich rewards in heaven. There have always been exceptions to this rule, however. Among the eight kinds of marriages described in the law, there is one form that is only an agreement between the lovers to be loyal to each other; in this form of marriage there is no religious ceremony, nor even a third party to witness and confirm the agreement and relationship, and yet by the law this is regarded as completely lawful a marriage as any other. It is quite plain from this fact that all girls were not betrothed between the age of eight and twelve years, and also that marriage was not considered a religious institution by the Hindus in olden times. All castes and classes could marry in this form if they chose to do so. One of the most noticeable facts connected with this form is this: women as well as men were quite free to choose their own future spouses. In Europe and America women do choose their husbands, but it is considered a shame for a woman to be the first to request marriage, and both men and women will be shocked equally at such an occurrence; but in India, women had equal freedom with men, in this case at least. A woman might, without being put to shame, and without shocking the other party, come forward and select her own husband. The Svayamvara (selecting husband) was quite common until as late as the eleventh century, A. D., and even now, although very rarely, this custom is practiced by a few people.

I know of a woman in the Bombay presidency who is married to a Brahmin according to this form. The first wife of the man is still living; the second wife, being of another caste, he could not openly acknowledge as his religiously wedded wife, but he could do so without going through the religious ceremony had she been of his own caste, as the act is sanctioned by Hindu law. The lawless behaviour of the Mahomedan intruders from the twelfth century, A. D., had much to do in universalizing infant marriage in India. A great many girls are given in marriage at the present day literally while they are still in their cradles; from five to eleven years is the usual period for their marriage among the Brahmins all over India. As it is absurd to assume that girls should be allowed to choose their future husbands in their infancy, this is done for them by their parents and guardians. In the northern part of the country the family barber is generally employed to select boys and girls to be married, it being considered too humiliating and mean an act on the part of parents and guardians to go out to seek their future daughters and sons-in-law.

Although Manu has distinctly said that twenty-four years is the minimum marriageable age for a young man, the popular custom defies the law. Boys of ten and twelve are now doomed to be married to girls of seven and eight years of age. A boy of a well-to-do family does not generally remain a bachelor after seventeen or eighteen years of age; the respectable but very poor families, even if they are of high caste, cannot afford to marry their boys so soon, but even among them it is a shame for a man to remain unmarried after twenty or twenty-five. Boys as well as girls have no voice in the selection of their spouses at the first marriage, but if a man lose his first wife, and marries a second time, he has a voice in the matter.

Although the ancient law-givers thought it desirable to marry girls when quite young, and consequently ignored their right to choose their own husbands, yet they were not altogether void of humane feelings. They have positively forbidden parents and guardians to give away girls in marriage unless good suitors were offered them.

“To a distinguished, handsome suitor of equal caste should a father give his daughter in accordance with the prescribed rule, though she have not attained the proper age.” – Manu ix., 88.

“But the maiden, though marriageable, should rather stop in the father’s house until death, than that he should ever give her to a man destitute of good qualities. – Manu ix., 89.

But, alas, here too the law is defied by cruel custom. It allows some men to remain unmarried, but woe to the maiden and to her family if she is so unfortunate as to remain single after the marriageable age. Although no law has ever said so, the popular belief is that a woman can have no salvation unless she be formally married. It is not, then, a matter of wonder that parents become extremely anxious when their daughters are over eight or nine and are unsought in marriage. Very few suitors offer to marry the daughters of poor parents, though they may be of high caste families. Wealth has its own pride and merit in India, as everywhere else in the world, but even this powerful wealth is as nothing before caste rule. A high caste man will never condescend to marry his daughter to a low caste man though he be a millionaire. But wealth in one’s own caste surpasses the merits of learning, beauty and honor; parents generally seek boys of well-to-do families for their sons-in-law. As the boys are too young to pass as possessing “good qualities,” i.e., learning, common-sense, ability to support and take care of a family, and respectable character, the parents wish to see their daughter safe in a family where she will, at least, have plenty to eat and to wear; they, of course, wish her to be happy with her husband, but in their judgment that is not the one thing needful. So long as they have fulfilled the custom, and thereby secured a good name in this world and heavenly reward in the next, their minds are not much troubled concerning the girl’s fate. If the boy be of rich or middle class people, a handsome sum of money must be given to him and his family in order to secure the marriage; beside this, the girl’s family must walk very humbly with this little god, for he is believed to be indwelt by the god Vishnu. Poor parents cannot have the advantage of marrying their daughters to boys of prosperous families, and as they must marry them to some one, it very frequently happens that girls of eight or nine are given to men of sixty and seventy, or to men utterly unworthy of the young maidens.